The Hidden Cost of Plastic in Healthcare

“I just want to say one word to you, just one word – plastics. There’s a great future in plastics.” These words voiced by the fictional character, Mr McGuire in the 1967 film, The Graduate, were truly prophetic as since 1950, plastic production has increased by a factor of 230 from 2 to 460 million tonnes per year.

Whilst plastic has enabled innovation in many industries including healthcare, this has come at an environmental and social cost which cannot be ignored. 98% of plastic is derived from fossil fuels, the industry produces 2 billion tonnes of CO2 per year and almost 40% of products are intended for single use. Compared to today, production is predicted to double by 2040, triple by 2060 and we can neither get to ‘net zero’ nor restore the planet to good health without considering plastic.

TOPICS WE WILL COVER:

1 / The environmental and health impacts of plastic in healthcare.

2 / Minimising harm through waste management.

3 / Segregating waste for sustainable disposal.

4 / Balancing sustainability and patient care.

5 / Are you looking to reduce single-use plastics in your facility?

The Environmental and Health Impacts of Plastic in Healthcare

Fossil fuel plastic causes death, disability, and disease at every stage of its lifecycle; impacting upon the health of the planet and the many species, including humans, which call it home.

Fossil fuel plastic causes death, disability, and disease at every stage of its lifecycle; impacting upon the health of the planet and the many species, including humans, which call it home.

Plastic is comprised of complex polymers and thousands of chemicals which can be persistent, bio accumulative and toxic including endocrine disrupters, a particular concern for the food and medical industries. Plastic is designed to be durable and in 2018, it was reported that 6.3 of the 8.3 billion tonnes produced persists as waste in landfill or the environment.

Human health impacts are predominantly experienced by those in lower Human Development Index countries, fence line communities, the vulnerable and extremes of age.

Healthcare organisations must be cognizant of their footprint; otherwise, the products and services procured and used with good intention will, through contributing to climate change and environmental ill health, fuel further demand for services at a time when they themselves are trying to reduce their own environmental impact. It is therefore welcome to see the NHS Standard Contract requiring action to be taken by the whole value chain to reduce the avoidable use of single use plastic which comprises 23% of the waste produced by the NHS, most of which is ultimately incinerated whether it sees clinical action or not.

The UNEP Global Plastic Treaty aims to ‘turn off the tap’ on single-use plastics and whilst healthcare may fall into the category of ‘essential use’, we must still aim to first, do least harm by reducing use whenever possible.

Minimising Harm Through Waste Management

Despite innovations in material science, bioplastic, reduction in medical device plastic mass, use of less-toxic polymers, reintroduction of reuseable products and recycling, we must be honest that for the foreseeable future, healthcare will remain dependent on many single-use plastic products.

One of the most important decisions a healthcare professional can make is when to open the packaging of a single-use device as once opened, the item becomes waste whether used or not. It’s therefore essential to move from a ‘just in case’ to a ‘confirmed required’ mindset. Staff responsible for preparing clinical areas like anaesthetic rooms must check the requirements of anaesthetists before items are opened.

An equally important decision is how to dispose of used items safely with the least environmental harm. Healthcare waste is deemed non-hazardous until proven or suspected otherwise and appropriate containers must therefore be available to accommodate all potential waste types for the specific clinical area.

Segregating Waste for Sustainable Disposal

Safe and sustainable management of healthcare waste provides clear guidance and its essential clinical, sustainability and waste management leads create supporting materials to help staff segregate waste correctly.

Ensuring waste is disposed through the correct waste stream using the most sustainable containers has a significant, measurable impact on the amount of plastic consumed, distance transported, method of treatment, whether the energy created can be utilised by the national grid and cost.

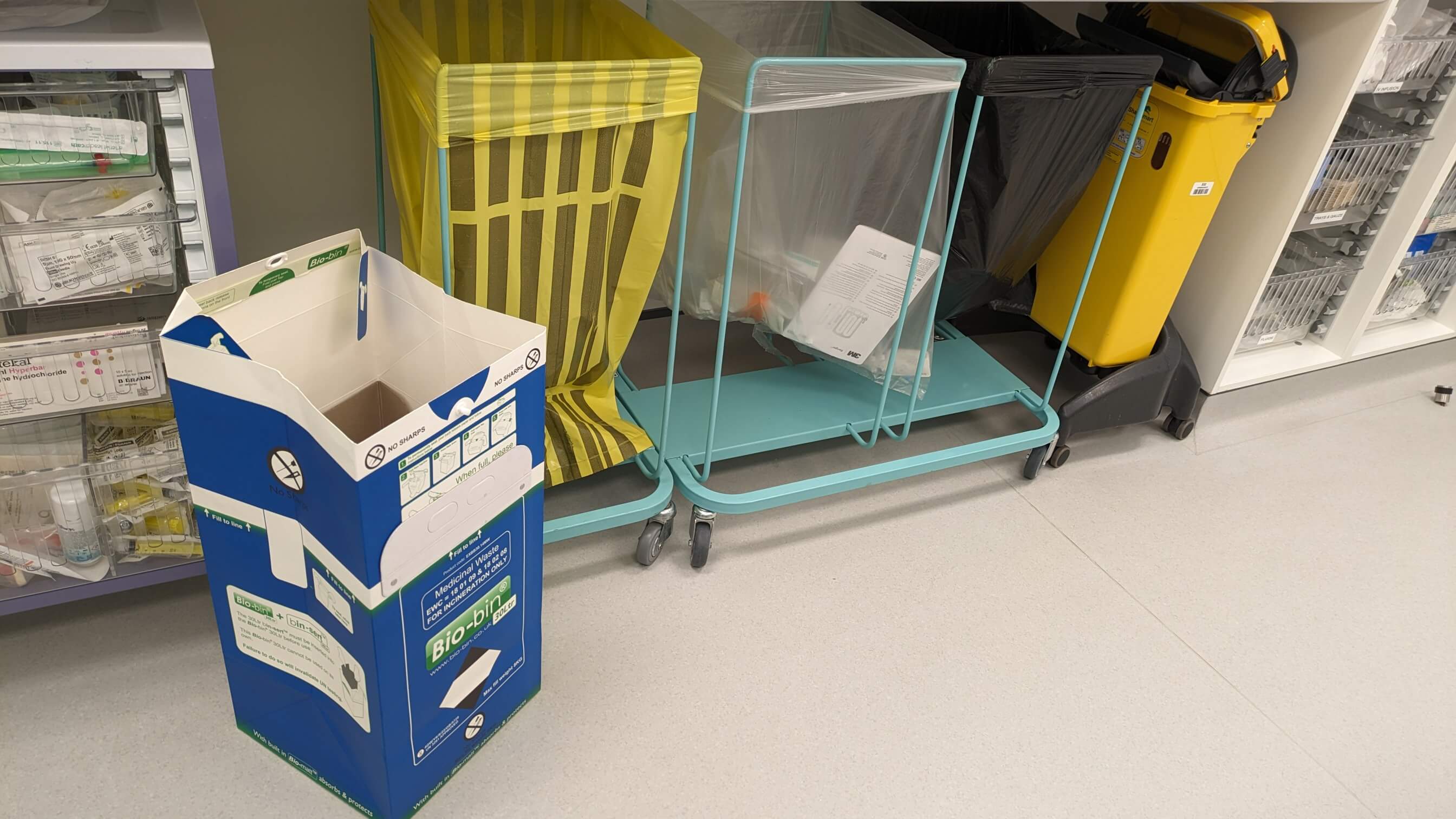

Mapping these pathways and calculating metrics for our different waste streams led to several changes. By moving to Sharpsmart reusable sharps bins, our 11-bedded critical care unit reduced the amount of (single-use sharp bin) plastic incinerated by 2.3 tonnes per year and through introducing blue Bio-bin containers into every bedspace, redirected 6.4 tonnes of medicinal waste (predominantly used fluid bags, syringes and giving sets) to the less environmentally harmful, non-hazardous waste stream.

This waste redirection followed an analysis of Health and Safety Executive Regulations, a local risk assessment and agreement the risk to staff from a giving set ‘spike’ which remained embedded in an intravenous bag was minimal. We communicated that all giving sets along with their attached bags of intravenous fluids/residual pharmaceuticals could be disposed of in Bio-bins and since making this change several years ago, no associated injuries have been reported.

The only pharmaceuticals not disposed through the blue waste stream are those with cytotoxic or cytostatic properties, hazardous sharps, or items contaminated during use. These are placed in the purple or yellow sharp waste streams respectively.

This ‘balance of probabilities’ approach to theoretical harm from a shielded giving set spike compared to the known increased environmental harm from overly cautious classification of healthcare waste as hazardous is a great example of a pragmatic approach to sustainability. Challenging existing processes which we continue to do because we’ve “always done it that way” is essential when plotting a path to truly sustainable healthcare.

Concerns over the space required for these additional waste containers were quickly allayed by the positive feeling arising from a visible reduction of the environmental impact of care. Demands on staff time reduced through fewer container exchanges and cost savings amounted to thousands from just one clinical area.

Reducing the demand pull for single-use items can be challenging if the infrastructure to support the re-introduction of reuseable devices has changed and whilst supporting and pursuing the principles of circularity, it’s essential to consider service demands and patient needs. For example, a reuseable bronchoscope on critical care is of little value when in transit for cleaning or being repaired which in our experience, can take weeks.

Every additional day a patient spends on the unit comes with an energy, plastic, drug and pollution cost; factors not always included in product life cycle assessments. Our approach is therefore to ensure continued availability of single patient use bronchoscopes and to support environmentally-ambitious companies in making devices as sustainable as possible.

Balancing Sustainability and Patient Care

Despite the use of composite materials and distinct lack of clues on packaging, we continue to separate plastic from paper never sure what can or will be recycled. Whilst items contaminated with a body fluid will primarily be directed toward the offensive waste stream (tiger bin), questions are often asked of why we do not recycle non-hazardous plastic waste. Is there evidence this poses a higher risk than a random plastic drinks bottle destined for recycling following a beach clean?

Despite the use of composite materials and distinct lack of clues on packaging, we continue to separate plastic from paper never sure what can or will be recycled. Whilst items contaminated with a body fluid will primarily be directed toward the offensive waste stream (tiger bin), questions are often asked of why we do not recycle non-hazardous plastic waste. Is there evidence this poses a higher risk than a random plastic drinks bottle destined for recycling following a beach clean?

As material complexity may currently preclude this pathway, future products and packaging must be designed to be reused, recycled or disposed of with minimal environmental impact whilst as an industry, we must be pragmatic about risk.

My personal journey exploring healthcare plastic and waste has thrown up all sorts of emotions. Plastic is simultaneously harmful and beneficial, but with the benefits received by those in countries with accessible healthcare system and the harms externalised to the planet and those less fortunate.

With the increased knowledge we now possess, we should at least acknowledge the harm, use products responsibly, communicate why, educate our peers and first, do least harm whenever possible.

Everyone has an equal right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health and from a climate and environmental perspective, health is everything; it’s why we care. The trusted voices of healthcare professionals can, as we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, cut through the noise and by including climate, environment and their impacts on health within our own professional development, we can become effective communicators inspiring others to act both in their personal and professional lives.

Richard Hixson is a Consultant in Critical Care Medicine, Physician Environmentalist, designer of CPDmatch, and co-founder of Healthcare Ocean. Richard’s interest is Global Goal 14, Life Below Water and he works with healthcare providers, supplier industries and NGOs to help improve the health of the ocean.

Are You Looking to Reduce Single-Use Plastics in Your Facility?

Introducing reusable sharps containers is a highly effecti ve way to reduce single-use plastics and improve safety for both staff and patients – we offer much more than sharps bins and collection service.

ve way to reduce single-use plastics and improve safety for both staff and patients – we offer much more than sharps bins and collection service.

Sharpsmart works with clinical teams within the four walls of your facility to streamline your waste management and ensure the most sustainable disposal solutions.

Feel free to contact us to learn more about how reusable sharps containers can help you and your hospital trust on the route to Net Zero.

Let's Talk!

Your time is valuable, and we don’t want to play hard to get. You can either phone us directly on the details listed on our contact page, or feel free to fill out this short form and one of our team members will get back to you as quickly as possible.